AI is moving faster than your strategy. Read more

Jan 23, 2026

3

min

Sustainability capital allocators sit at the intersection of finance, regulation, and real-world outcomes. They are expected to deliver competitive returns while proving measurable environmental and social impact.

One number frames the urgency: emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs) need to mobilize about $2.4 trillion per year in climate finance by 2030, including $1 trillion in external finance.

The gap is not “capital”, it’s conversion

In 2023, global climate finance reached about $1.9 trillion, but only around $332 billion flowed to EMDEs, which is about 14% of the annual EMDE need by 2030. International private climate finance to EMDEs rose from $17 billion in 2021 to about $36 billion in 2023, but the same analysis says it must grow 28-fold to reach $1 trillion per year by 2030.

Zooming out beyond climate, the UN Financing for Sustainable Development Report 2024 estimates SDG financing and investment gaps at between $2.5 trillion and $4 trillion annually.

Translation: capital exists, but the system is not converting “demand for impact” into “deployable allocations” fast enough.

The allocator workflow (where it breaks)

Where it most often breaks in EMDE contexts: barriers like limited visibility of bankable projects, data and capacity gaps, and complex de-risking mechanisms that raise transaction costs and complicate deal structuring.

The challenge stack (what allocators fight daily)

1) Not enough “bankable” pipeline at the right ticket size

Institutional investors often face minimum ticket sizes because fixed costs like diligence and compliance do not scale down. Many EMDE climate projects are too small or fragmented to meet minimum ticket-size requirements, which helps explain why institutional investors account for only about 1% of private climate finance to EMDEs in 2023.

2) Data is still a binding constraint, not a nice-to-have

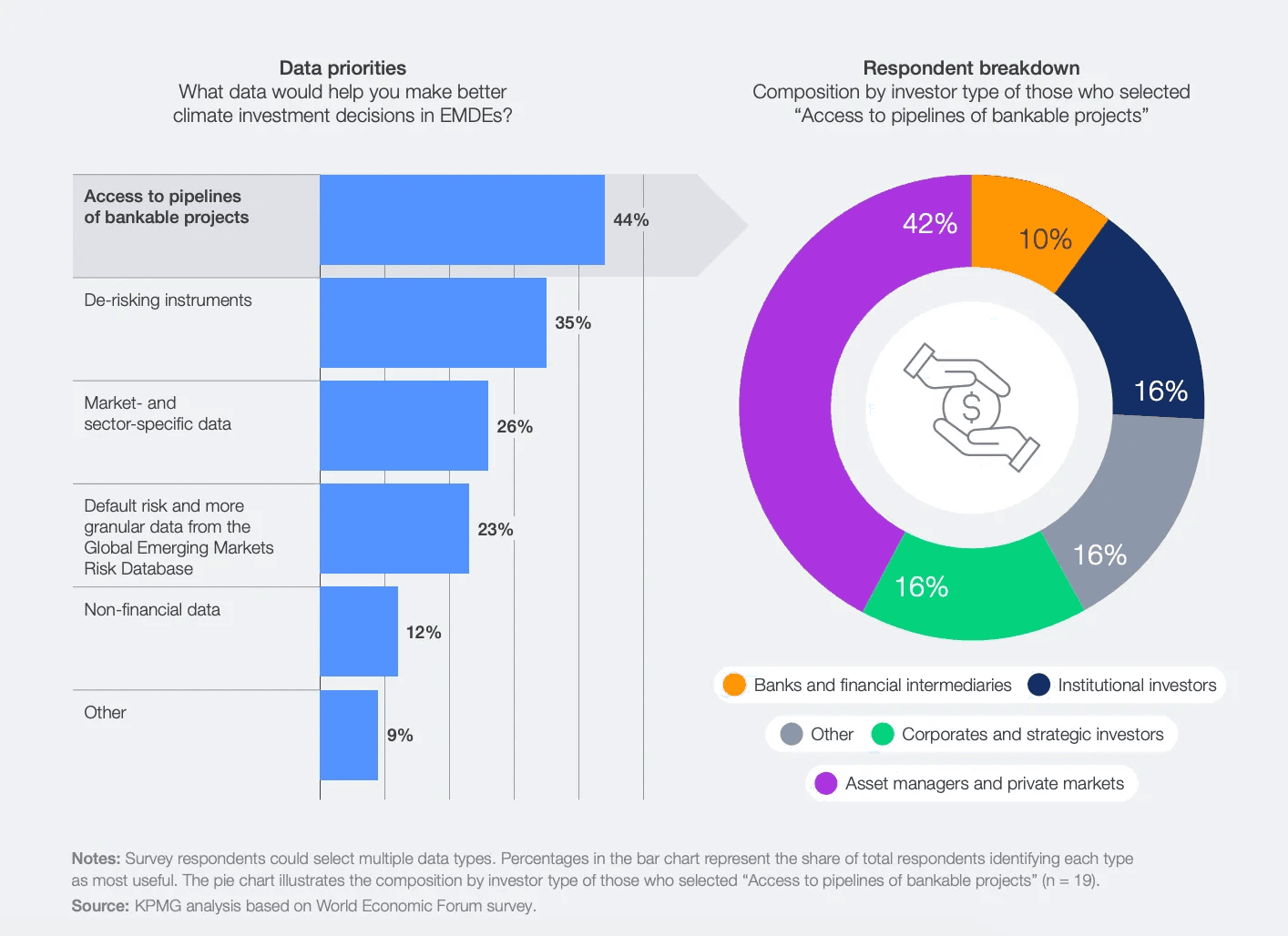

In a survey, 32% of respondents ranked better data and transparency as the most effective tool to mobilize private climate finance to EMDEs. In the same survey results, 44% of respondents cited access to pipelines of bankable projects as the most critical data needed to support climate investment decisions.

Image source: WEF

3) Mitigation dominates because cashflows are clearer

Private climate finance in EMDEs is heavily concentrated on mitigation, with 96% of flows, while adaptation accounts for about 1% (and dual benefit 3%) in 2023. This imbalance matters because adaptation is often where vulnerability is highest, but monetizable revenue models are weaker.

4) FX and macro risk are not “side issues”

Heightened political and foreign exchange risks and high cost of capital are structural barriers. Even a strong project can become uninvestable if revenues are local currency and financing is hard currency without affordable hedging.

5) De-risking exists, but it is often bespoke and slow

Blended finance, guarantees, first-loss structures and climate insurance exist, but are frequently complex, accessed deal-by-deal, and contribute to transaction friction. Simplifying access to guarantees and blended finance tools is shown as the most popular recommendation for improving mobilization through DFIs and MDBs among surveyed investors.

6) The private sector is essential, but not a monolith

Breaking down down private climate finance to EMDEs by investor type, shows commercial and investment banks as the largest group at 40% in 2023, followed by corporates at 35% and households/individuals at 23%. Institutional investors are a small slice at 1%, which signals a structural mismatch between “large pools of capital” and “deal formats that fit”.

A practical playbook for allocators

These are not silver bullets, but they reduce friction and make capital more deployable without lowering integrity.

Standardize the minimum data spine: Define a short list of portfolio-wide metrics that every manager must report, then expand only when the data is decision-useful.

Fund the measurement capacity: Treat ESG and impact data like financial reporting, not a side task, because even leading private market managers report persistent difficulty producing emissions and indicator data.

Use catalytic structures intentionally: In EMDE strategies, plan for guarantees, blended finance, or first-loss layers as a design feature, not an exception, because affordability and risk constraints are structural.

Separate “alignment” from “outcomes”: Run two dashboards, one for taxonomy or policy alignment and one for measured outcomes, since mitigation and adaptation flows behave very differently in practice.

Pre-empt greenwashing with evidence packs: Build a repeatable “claims file” for each product (methodology, data sources, limits, engagement record) so marketing language stays defensible.

For allocators, this next chapter of sustainable finance is not about discovering more capital, but about proving that capital can be steered, structured, and stewarded in ways that genuinely close the climate and development gap rather than simply reshuffling portfolios.

The allocators who will matter most are those willing to wrestle with messy data, experiment with catalytic structures, and lean into credible impact measurement so that every dollar does more than signal intent, it demonstrably shifts real-world outcomes.

About Penomo

Penomo is a digital asset infrastructure platform specializing in tokenized energy and AI infrastructure financing.* Through tokenization technology, Penomo is streamlining financing processes, enhancing liquidity, and enabling efficient financing for the global energy transition and AI expansion.

The time to lead is now!

→ Curious if tokenized capital fits your project? Take 2 minutes to find out.

Connect with us: Website | X | Telegram | TG Announcements | Discord | LinkedIn